Here is a movie I will not watch:

A recovering alcoholic’s feelings of inadequacy and guilt drive him further apart from his family, pushing him back to drink. His wife and young child withdraw from him as he becomes unpredictable and abusive.

But change it slightly:

A haunted hotel leverages a recovering alcoholic’s feelings of inadequacy and guilt to drive him further apart from his family…

…and you have The Shining, one of the best horror movies ever made. Drama plus horror somehow intensifies the horror and underlines the theme.

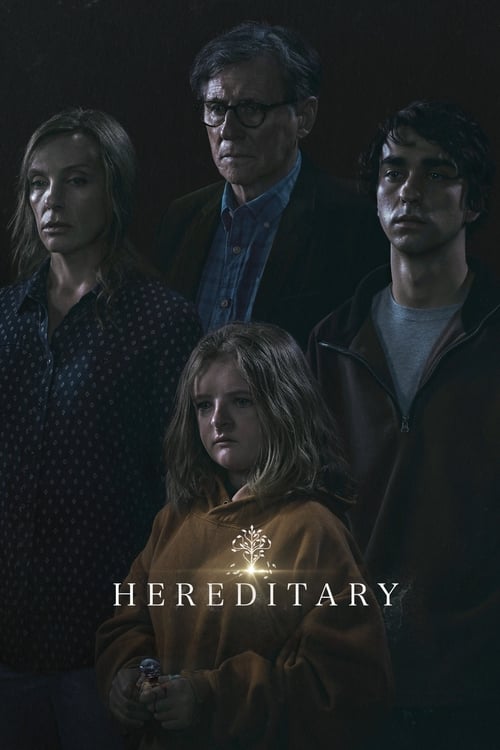

Stephen King is a master of this storytelling, but plenty of other great movies do this as well. Regan’s carotid angiography left many Exorcist viewers faint. And of all the terrifying events in The Sixth Sense, the scene that has stuck with me for over twenty years is watching a mother poisoning her own child for no apparent reason other than wanting to feel needed. Hereditary writer and director Ari Aster seems to want to join those ranks. It is, at least at the front part of the movie, a family drama. “How can people behave this way?” I thought while watching, knowing for a fact that people behave this way and worse. Especially when we get to That Scene.

Milly Shapiro plays Charlie in a way that is both inexplicably repulsive and supremely vulnerable.

I will not talk about That Scene. There are no creature effects, precious little gore. There is nothing that typically characterizes horror in a genre film. It is just the culmination of several irresponsible decisions spread across the family unit resulting in a terrible, senseless tragedy. People who have seen the movie already know what That Scene is; there is no other scene deserving the name. Those yet to see it will recognize it the instant it happens. They will probably see it coming. However, there is nothing supernatural about it. Or is there?

Tony Collette’s Annie is a complex bundle of doubt, frustration, and guilt. The emotional center of the movie lives in her face. It’s a performance that is difficult to put into words, and almost everyone and everything makes space to give her room. The possible exception is Milly Shapiro, who plays pre-teen Charlie in a way that makes her repulsive and makes you feel guilty for feeling that way. Gabriel Byrne (the dad, Steve) is dutifully attentive, like he’s read a manual about being a good husband. Alex Wolff’s Peter could so easily be the stereotypical stoner teen. Instead, he plays a child who is has withdrawn from the world because he’s terrified of stepping into it. He has good reason.

Much of the story is told by showing Annie reacting to something, then showing us what she sees.

The movie’s human action is so unsettling that the supernatural horrors actually come as a relief. The film becomes a series of jump scares, gruesome effects, and weird voices. Don’t get me wrong, some of this material is legitimately scary. The séance is as frightening as any of the gruesome scenes to come, and it’s just acting and a tiny amount of practical effects.

But these scares are of a more typical nature. We have seen people float creepily in corners. Monsters predictably chase people down hallways. Old naked people are once again used to inspire disgust. We are back in the horror fan’s native country. It feels more comfy than the icy silences and barely disguised contempt of a family in meltdown.

Visually, Hereditary is dark, claustrophobic, and beautiful. For example, the opening scene is of the interior of a dollhouse. We zoom in, and in, and into a bedroom. And then, seamlessly, the dollhouse becomes the real world. People move, and the story begins. It is, perhaps, a metaphor for movies themselves. That’s too precious a thought; it is, more likely, foreshadowing the movie’s end. Which I should not discuss, but I will say this. The first half of the film is about how people making poor, lazy, and convenient choices can wreck lives and destroy relationships. The second half of the movie absolves everyone of responsibility.

And that’s the unfortunate, frustrating truth about Hereditary. While supernatural forces underline the themes of movies like The Shining and The Exorcist, Hereditary’s ghosts just cross it out.

Annie’s art certainly takes a dark turn.