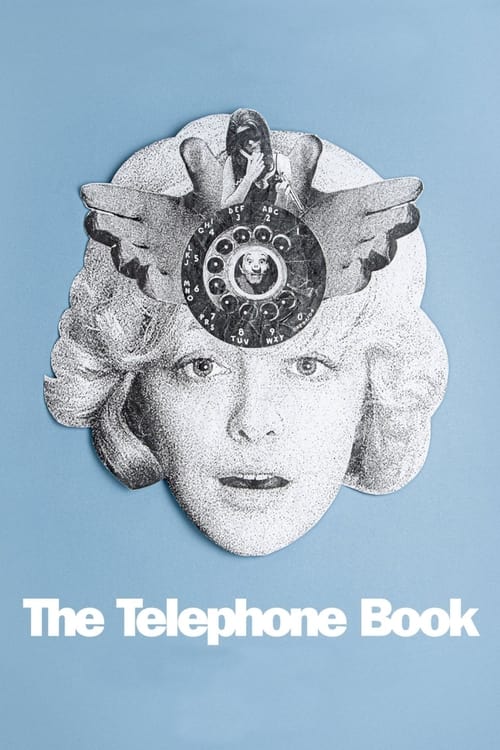

Here’s the thing about The Telephone Book. The experience you have depends a lot on your mindset going into it. Perhaps that’s why it’s languished, but survived, in obscurity for fifty years. The only movie written and directed by Saturday Night Live writer Nelson Lyon, this bizarre black-and-white X-rated film opened to terrible reviews but survived in bootlegs long enough for Vinegar Syndrome to get their hands on a 35mm print, which they restored and released in 2013.

Alice is a young woman who lives alone in New York in a small apartment. Alice has decorated her apartment with pornographic wallpaper and strewn with pornographic magazines all over the floor. She paces in her bedroom, overcome with ennui. The phone rings, and baritone voice speaks with the warm, deliberate tone of a film narrator. “Hello there,” he says. “I’d like to talk to you very seriously for a moment about your beautiful tits…”

The actual actor behind the voice is Norman Rose. Rose worked during WWII as a radio newscaster for the Office of War Information. Afterwards, he made a career out of voice acting, film narration, and commercials. He’s most familiar to people of a certain age as the voice of Juan Valdez (example).

Alice is played by Sarah Kennedy, who is probably also familiar to people of the same age. She was a regular on the sixth season of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, and then was a frequent panelist on The Match Game. We are two characters deep into the movie, and both of them are familiar. More friendly faces will follow.

Just as Norman’s phone call is getting interesting, though, we jump cut to a smirking man in a business suit facing the camera. He brags for a bit about how awesome he is, then tells us how he used to make dirty phone calls but is entirely well now. And thus the tone is set.

The Telephone Book is a movie about Alice’s quest for sexual liberation and fulfillment as she seeks the man behind the mystery phone call, but Lyon continuously undercuts the eroticism of the movie with jarring cuts to distasteful people being distasteful.

Acclaimed actor Jill Clayburgh as “Eyemask,” Alice’s more experienced, and far more jaded, confidant.

It is a satire of sorts of the nudie film, specifically the “young woman exploring her sexuality” movies that were common in the late sixties to early seventies, as the film industry dragged itself out of decades of oppression from the Hayes Code. Instead of encountering a series of older, more experienced, more suave men who “instruct” her, Alice’s adventures lead her to men (and women) who are self-absorbed, sexually dysfunctional, or find her threatening. Even her caller, Mr. Smith, hides himself behind a phone and then, when they meet, a mask.

This is not a film made by nobodies. Distinguished English actor Barry Morse is a stag film star who dismisses Alice. “I think my right leg is free,” he says. “That’s about all that’s available at the moment.” Morse had already made a name for himself on US Television playing Lt. Philip Gerard in The Fugitive. The exhibitionist who flees Alice when she flashes him back is Roger C. Carmel, known to Star Trek fans as Harry Mudd. Already successful character actor and HB Studio instructor William Hickey (Prizzi’s Honor) is the “Man in Bed,” whose priapism costs him his wife and family. Alice’s confidant is Jill Clayburgh, a serious actress who won best actress at Cannes for her starring role in Paul Mazursky’s An Unmarried Woman. Andy Warhol collaborators Ultra Violet and Ondine have appearances. Even the film’s original intermission, now lost, was Warhol eating popcorn. These familiar faces — at least, familiar to my generation and older — make watching an already discombobulating film even more so.

You should refer to me as Mudd the First, ruler of this entire sovereign planet.

Until the end, the movie rarely approaches the pornographic. Lyon frames the most graphic scenes for humorous, not erotic, effect. Kennedy he treats with much more affection. The last ten minutes switch to crude, grotesque color animation that looks like Terry Gilliam trying to bite Rocky & Bullwinkle’s style in a commission for PornHub. This is explicit and feels out-of-place. Maybe there’s genius here flying over my head, but I felt it ended the film on an ugly, discordant note. It’s probably this bit that earned it the X rating.

Otherwise, the movie is gorgeous. It switches effortlessly between comic, documentary, and abstract. It’s easy to see why Dan Rowan recruited her for Laugh-In on the strength of this film. She shares that story in this interview, which she tries to explain why Rowan found her so interesting without explaining to the interviewer what specifically The Telephone Book was about. In a movie with so much sex, Alice is the only one having fun.

That’s probably also true of most of the contemporary audience who — no doubt — left the theater feeling like they’d had a practical joke played on them. Perhaps they had.

Hey pig, there’s a lot of things I hoped you could help me understand.