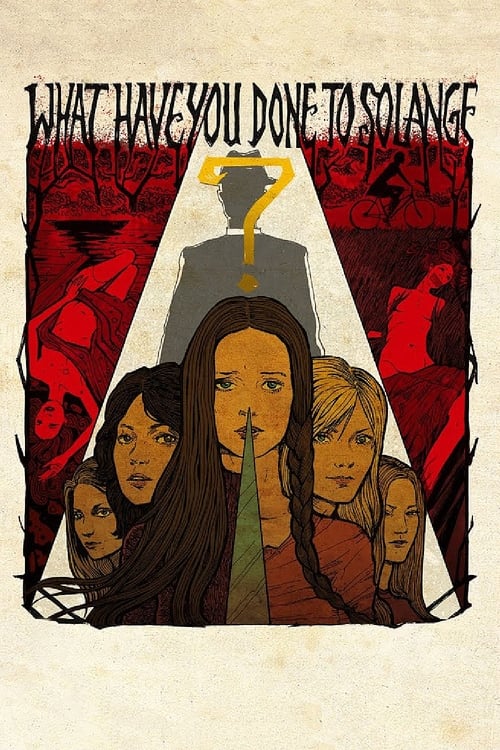

Sometimes you settle in to watch a melodramatic, over-the-top Italian serial-killer giallo and wind up getting something different. This was the case with What Have You Done to Solange?. The movie is all of those things, but the film is darker and the protagonist sleazy enough that I was often uncomfortable watching it.

When students at a girls-only Catholic school start turning up murdered, suspicion falls on gym teacher Enrico “Henry” Rossini (Fabio Testi). Henry is not subtle about his interest in the students and has a reputation for inappropriate behavior. His wife Herta (Karin Baal), an attractive but very severe woman, is well aware and losing patience. But that doesn’t stop Henry from setting up his current flame, Elizabeth (Cristina Galbó), in an apartment near the school.

Dead catholic schoolgirl in your love-nest, Henry. Not a good look.

The murders themselves are particularly misogynist if not particularly graphic. The father of one of the victims asks an inspector: was she raped? “In a certain sense,” he replies and pulls out x-rays that leave no doubt about how the girls were killed.

Henry is, of course, not guilty. At least of being a murderer. And he turns detective to clear his name (of murder), in the process learning of the fate of a mysterious student named Solange (Camille Keaton, Buster’s granddaughter), the reason the murdered girls were chosen, and the unsettling motivation for the method of their murder. In the process, he enlists his wife’s help, reviving their relationship and turning his attentions away from the young girls under his care.

What Have You Done to Solange? is practically the definition of a problematic movie. There’s a lot here that I have questions about. Although other critics online seem unsure whether these are college students or high school students, it doesn’t really matter. The faculty’s relationship with the students is clearly paternalistic. They speak to the girls as though they are children, lecture them as though they are children, and the girls act like children. I do not know anything about European Catholic schools in the 1970s, but I got a realistic enough high-school vibe to be seriously wigged out by Henry’s behavior. The fact that we get not one but two group shower-scenes didn’t help matters. The scenes’ point is to hear the student’s private chatter about the murders, but the director justifies the slow, lingering pans by showing us that someone on the school’s staff has a convenient peep-hole into the locker room.

I’m not mad you “date” your students, Henry. Just jealous.

Perhaps worse than Henry’s behavior is that of the rest of the faculty, who mostly roll their eyes. They do not blame Henry, though. He would not be this way if Herta was not so severe. Later, Herta learns something about Henry’s dalliances that seems like a technical distinction to me but apparently makes all the difference to Herta. She literally lets her hair down. Instead of harrying Henry, she begins seducing him again.

The thematic message this sends is upsetting. Perhaps Henry’s relationship with Herta is on the rocks because she has been a bit of an ice queen. I can accept that. But to suggest Henry’s sexual predation on students under his authority and responsibility are somehow Herta’s fault is a bit much for me to bear. Henry should have been run out of town on a rail years ago. Herta may be willing to forgive him, but I’m not.

Perhaps even more worrisome is the motivation for the murders. I would love to say more about but don’t feel like I can without spoilers. Let’s just say that if you blame the victims of serial killers, I think it should feel a bit more like cheesy melodrama and a bit less like you, the director, think they are getting their just deserts.