There’s a quiet scene in the middle of Night Moves that stands out like an emergency flare. Private investigator Harry explains a chess game from 1922 that he’s been studying. “Black had a mate, and he didn’t see it. Queen sacrifice,” he says, nudging pieces around the travel chess set next to his bourbon bottle. “And three little knight moves. He played something else, and he lost. Must have regretted it every day of his life. I know I would have.” There’s a beat. “Matter of fact, I do regret it,” Harry says. “And I wasn’t even born yet.”

This is the understated but extraordinary screenwriting of Scottish author Alan Sharp in action. Quiet, but clear enough to make alert movie-watchers sit up and take notice. “This means something,” I said, fighting down the urge to make a volcano out of mashed potatoes. It does, but Sharp will not let you in on it. If you want to figure it out, you’re on your own.

“You beating yourself?” asks Paula when she sees Harry studying his chess board, and it’s so deadpan I didn’t even catch the the double entendre until I started writing this.

To be honest, while i was watching this movie I kept wondering if it was worth the effort. I’m a sucker for private-eye stories from just about any era, but I felt Night Moves was using the genre as sheep’s clothing. It suckered me in with a noir promise but was giving me romantic drama instead. When it was over I went “huh, OK” and moved on to the next thing. But over the last few weeks I just keep coming back to this movie. Thinking about it, the queen sacrifice, and the three knight moves.

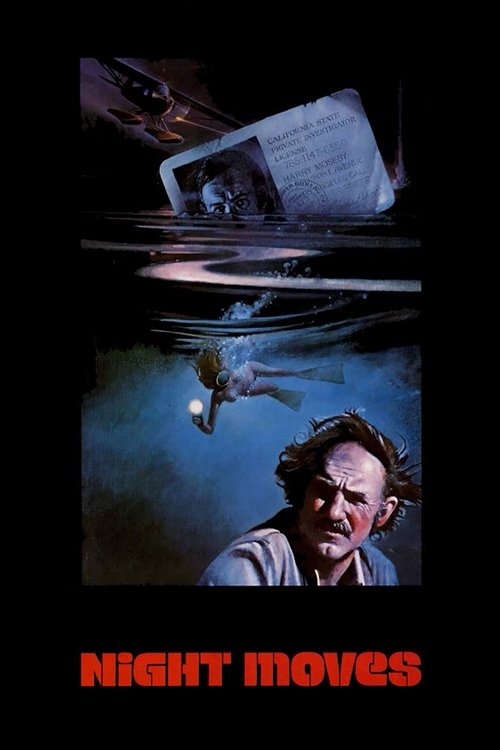

Harry (Gene Hackman) is a private detective. His work lacks the romance of Sam Spade — mostly divorce cases out of Los Angeles. His own marriage to Ellen (Susan Clark) isn’t fairing much better. Hoping to surprise her downtown, he instead sees her walking home from watching an art film with her lover. He tails his own wife like one of his subjects, which interferes a bit in his work on his current case: tracking down runaway teenager Delilah (Melanie Griffith) for her movie-star mother.

Harry and Ellen’s problem is that they seem to have grown apart. Harry is an ex pro-football star whose primary intellectual interest is chess. Ellen runs a successful furniture store and likes to watch French New Wave movies with her friends. When Harry tracks down her boyfriend, Marty, he turns out to be a bookish intellectual who needs a cane to get around — and, honestly, Marty and Ellen seem like a better fit for each other.

Delilah’s mother Arlene (Janet Ward) is a fading actress, sliding into irrelevance and alcoholism. Delly has run away, but Arlene is less concerned about her safety than she is access to Delly’s trust fund. In fact, Arlene puts some moves on Harry while he’s there to discuss the case, which is especially creepy.

Delly takes after her mother. Harry hits up Delly’s ex-boyfriend (James Woods). “You got any idea where she could be? Is she visiting friends? Meditating? Did she join a commune?” The boyfriend snorts. “Delly’s idea of a commune is her and a guy on top of her.”

Marv the stuntman is so punchable it comes as a relief when it finally happens.

This is one thing that has kept me coming back to this movie repeatedly. She’s named after a Biblical sexual predator who takes money to rob Samson of his strength, but her nickname suggests some place you stop in for a quick bite when you’re feeling peckish and in the neighborhood. This reflects how almost all the men around Delly react to her. They claim she is a force of nature, a superhuman and irresistible vamp devoid of any genuine feeling. But when we meet her, she’s… not. She’s a teenager, and Harry easily deflects her clumsy attempts at seduction by simply, and pointedly, ignoring them. She hasn’t overwhelmed these men; they’ve taken advantage of a naïve child. The stories they tell about Delly are their attempts to absolve themselves of any responsibility. “You’ve seen her,” says one lover, old enough to be her father if not her grandfather. “God, there ought to be a law.”

“There is,” says Harry, and almost, but not quite, raises an eyebrow.

Arthur Penn’s direction here is critical to the script. Harry on the job is professional, stoic, only the slightest bit judgmental. Harry chasing down his wife’s boyfriend is impulsive, frustrated, impotent. Delly, built up to be the femme fatale for the first half, never gets the camera’s full attention when she inevitably takes her top off. Just as Harry pretends not to notice, Penn’s framing puts Delly’s seduction attempts in the literal background. Paula (Jennifer Warren), Delly’s step-father’s girlfriend and an adult woman more Harry’s type than Ellen, is almost always in the foreground.

“How do you resist?” Paula asks him as Delly wanders around the guesthouse wearing only one of Harry’s dress shirts.

“Oh, I just think good, clean thoughts. Like Thanksgiving, George Washington’s teeth,” he says.

The same trick does not work against Paula.

Airports were always miserable, weren’t they?

It’s hard not to say too much about this movie, as you may have noticed. While I initially dismissed it as a minor noir that was overwhelmed by personal drama, I kept being drawn back to it over and over. I’d be brushing my teeth, or playing a video game, and I’d think: where is the queen sacrifice? Which ones are the knight moves? That ending that seemed to come out of nowhere? Did it really?

Night Moves is a smaller, much less famous film but pulls the same trick as 1967’s In the Heat of the Night and 1996’s Fargo. There’s a story there, but it’s not the one you think it is. Then the end of the film takes a sudden left turn, out of nowhere, and you have to put all the pieces together on your own. It’s a deeply unsettling at toxic male sexuality, but it says a lot about everyone’s ability to delude themselves into thinking they are the victims, even when they are not. It’s a topic Sharp, who married four times and walked out on his second wife and newborn daughter, knew something about himself.

If you want to think about these things, certainly spend time with Night Moves. If what you’re looking for is some clever, twisty, melodramatic noir, maybe pick up something from the less navel-gazing 40s.

Me, driving around, just thinking about the movie.