The opening shot is of a graveyard. Text appears on the screen: “This is the story of lost men and lost souls. It is a story of vice and murder. We make no apologies to the dead. It is all true.” And so begins this almost-true dramatization of the Burke and Hare murders of 1828. This being a historical film, a little context will help.

In the latter half of the 18th century, anatomical researchers were only allowed to use the cadavers of executed murderers for their study and lectures. But by the early 19th century, an increasing supply of medical students coupled with a decrease in executions outstripped the supply of legal corpses. The result was an increase in grave-robbing supplying the corpse black market. Inevitably, William Burke and William Hare realized they could provide a superior product by selling direct. They killed at least sixteen people and sold the bodies to Robert Knox, a famous medical lecturer.

Once caught, Hare testified against his partner and was released near the English border. He was never heard from again. The English, guiding light of civilization, hanged Burke. His corpse was dissected, his skin used to make a calling-card box, and both are still displayed in museums.

Knox, being both famous and rich, was not prosecuted. However, his reputation and career did take a significant hit. I am assured by other wealthy people that this is actually a worse punishment than being executed and turned into gruesome knick-knacks.

“Have you considered buying in bulk?”

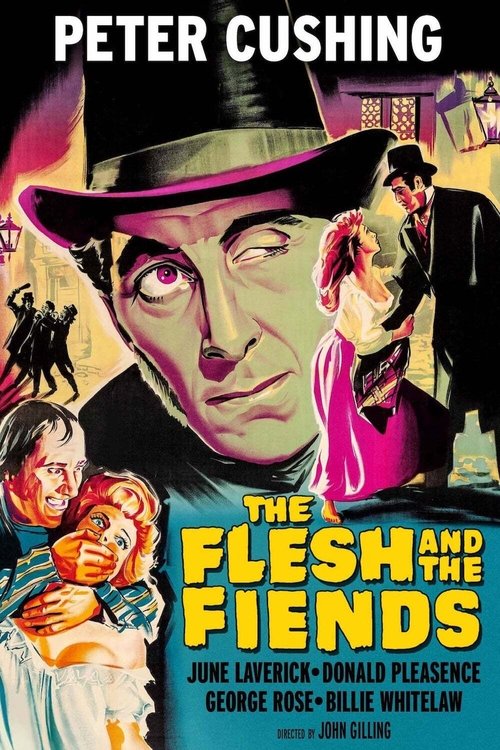

This dramatization is the second attempt by writer/director John Gilling, who wrote the screenplay in 1948’s The Greed of William Hart. This earlier effort was also a retelling of the Burke and Hare murders, but English censors insisted all the names be changed. In 1960, he was allowed to keep the historical references. In another stroke of luck, he put together an ensemble cast of extraordinary actors, some of whom --- like Cushing --- had just achieved stardom. Others, like George Rose and Billie Whitelaw, were on the leading edge of a significant career.

Peter Cushing is the historic Doctor Knox. Knox is well-liked by his students but tends to turn aggressively self-righteous when amongst his peers. He certainly isn’t particular about where the cadavers are coming from. Cushing’s shifty performance implies that Knox may have known that people were murdered specifically to sell to him.

Cushing is fresh off his Hammer stint as Victor Frankenstein in The Curse of Frankenstein and Von Helsing in Horror of Dracula. Here, too, the director takes advantage of Cushing’s facility with elaborate medical props and choreography. He really is good at that kind of thing, even with heavy makeup nearly closing one eye to match the historical Dr. Knox’s smallpox disfigurement.

Today, class, we are going to discuss the unintended consequences of legislative overreach.

Donald Pleasence portrays Hare as the mastermind of the murders, clever and amoral but lacking the strength or stomach to carry out cold-blooded murders. I’m used to seeing Pleasence in very one-dimensional roles: Blofeld in You Only Live Twice or Loomis in far too many Halloween films. I have never really understood why he was ever a big name. But the way Pleasence plays Hare’s cunning sleaziness as a foil against Burke’s cheerful sadism is a revelation.

Burke is played by Shakespearian actor, Tony award winner, and murder victim George Rose. One of Rose’s most famous roles was Alfred P. Doolittle, Eliza’s “undeserving poor” father, and it was for that role that he won his first Tony. His performance as Hare came sixteen years earlier and bridged the period between his Shakespearian acting and Broadway career. Known in both for his comedy roles, he plays this role with a weird sadistic, cruel dark humor. If you can imagine Chico Marx as Pennywise, you would not be far off.

Like My Fair Lady, The Flesh and the Fiends is about educated classes exploiting the impoverished and ignoring their humanity. The intersection between the two classes is the romantic subplot between Knox’s student Chris and Mary, a prostitute. Chris stands up for Mary’s honor in a bar, and they end up romantically entangled. Neither belongs in the other’s society, however. Chris expects Mary to transform into a proper middle-class English housewife, and Mary finds Chris’s scholarly dedication and upper-class sensibilities suffocating.

“Oh, Chris. You are the most lifeless stiff in this movie filled with corpses.”

The real Mary Paterson was a victim of Burke and Hare. Although often assumed to be a prostitute, research suggests she was just a young working-class woman. Chris is a fiction; Mary did have a medical student beaux, but that ended when she became pregnant. The real Mary’s boyfriend was affianced to a more suitable woman.

Mary, portrayed by Billie Whitelaw, is seductive and awkward, sorrowful and rebellious, repentant and wild. In the climax of the movie, she encounters Burke and Hare looking to restock. The result is an extraordinary performance between Whitelaw, Rose, and Pleasence with some of the best straight-up acting you can expect to see in low-budget, early-60s horror films.

It will come as no surprise that Whitelaw was on the verge of an extraordinary turn in her acting career --- leaving behind the floozy roles to become Samuel Beckett’s favorite actor and collaborator for two decades. Most people, however, will have encountered her before as Aughra, the wise woman who sets the Gelflings on their journey in The Dark Crystal.

“Shit, where did I put my mace?”

Many versions of The Flesh and the Fiends have been released over the years, in many different edits. It was actually shot and edited with alternate takes. One set was for the English censors. The other, with fewer blouses, for continental European release. The Kino Lorber version I watched was nicely, if imperfectly, restored and was the continental version. The Flesh and the Fiends is a low-budget, occasionally ponderous film. But it has a great script, sticks relatively close to the story, and has an extraordinary cast of actors in it. If you are a fan of this period, it is well worth your time.