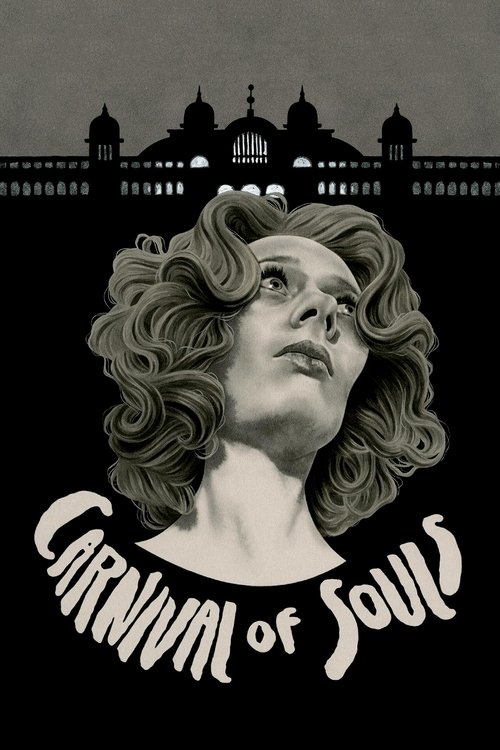

1962’s Carnival of Souls is hard to place somewhere along the typical (and useless) one-dimensional good/bad axis we typically use for movies. My first copy was an autographed “Mike Nelson Collector’s Edition” made way back in 2005 before Nelson got Rifftrax off the ground. My latest copy, and the edition I used for both the screenshots and this review, is a Criterion Blu-Ray. It took several watches for me to realize this “bad” movie was actually “good,” although maybe not quite in the way we usually think about good movies.

Herk Harvey — whose day job was as a director and producer for industrial film company Centron Films — directed and produced. His Centron colleague, John Clifford, wrote the screenplay in three weeks. It will come as no surprise that certain elements of the film have a kind of 1950s educational-short quality to them. The amateur cast doesn’t help matters. Carnival of Souls was a passion project for Harvey, who was drawn to the ruins of the Saltair II resort on the Great Salt Lake just as his main character, Mary Henry, was.

When we join the action of the film, Mary is a passenger in a car with several other young women. Another car pulls up and the two men inside challenge the driver of Mary’s car to a street race. There’s a lot of hard driving, and then as they drive neck-and neck across a bridge, the cars trade paint and Mary’s car plunges into the river. Three hours later (we are told), Mary — in shock and looking bedraggled — hauls herself up onto a riverbank and into the startled arms of the team dragging the river for bodies.

So this is the Internet? But I thought it was a series of…

We rejoin Mary an unspecified amount of time later, as she plays a pipe organ in the warehouse of a factory. Her mentor comes in, and they talk briefly about Mary’s upcoming placement at a church in Salt Lake City. He is enthusiastic. “You’ll make a fine organist for that church,” he says. “Be very satisfying to you, I think.” “It’s just a job to me,” Mary shoots back. “I’m not taking the vows. I’m only going to play the organ.”

Mary — feeling chatty for the only time in the movie — explains further to John Linden, a fellow lodger at the boarding house in Salt Lake. “To me, a church is just a place of business,” she tells him. “People seem shocked because I took a job in a church, and I regard it simply as a job. I’m a professional organist and I play for pay, that’s all.”

“Oh, I must have peeked through her bedroom window hundreds of times.”

John says: “Thinking like that, don’t that give you nightmares?”Mary certainly has nightmares, some of which invade her waking moments. She keeps seeing people where there are none. Drowned, pasty corpses walking around, leering at her, sometimes even sidling up close behind her when she thinks she’s alone in her rented room. She is also deeply fascinated by the abandoned pavilion on the shores of the lake. Everyone else in town shrugs the place off, but she’s obsessed with getting inside.

Candace Hilligoss’s performance as Mary is often distant and alien. John remarks on this later. “You seem sort of cold,” he says. “This morning when I brought you the coffee, you were friendly.” And it’s true; in the coffee scene with John, Hilligoss acts like any other leading lady of the time. She seems, for the only time in the movie before or after the accident, to actually be alive. In any other scene, she seems very distant — even from herself. Coffee with John is crucially important, here, in this amateur film. It helps show us that Mary’s cold exterior is an intentional choice.

“I’m gonna wash that man right out of my hair…”

Harvey’s fascination, though, is clearly the abandoned Saltair pavilion. We see it as only a silhouette on the horizon, but later Mary gets to explore the place in depth, wandering dazed through abandoned ballrooms and decaying amusement park rides. Places like these — designed for crowds and noise — can feel extremely unsettling alone.

I do not know whether Harvey was aware of the concept of “liminality,” broadly described as a sort of being in-betweenness or in states of transitions — but if he was an expert, he could have hardly done any better. The camera often focuses on borders — between shore and water. Conversations happen in doorways and hallways. When we see Mary bathing, it’s shot from another room. Mary’s accident happens on a bridge, and we have also caught her in the middle of several liminal states — making the change from child to adult, student to professional, moving from Kansas to Utah. And, of course, being the only survivor of a crash that took the lives of four others.The cinematography, acting, and a subtle script make this movie extremely interesting during repeated viewing. In this, Harvey was also aided by his tiny budget. Carnival of Souls seems to owe a lot to French New Wave, with hand-held cameras, rough takes, and on-location shooting, making the movie seem more real and immediate than anything shot on a soundstage in the 1960s.

She’s got a great set of pipes.

Where the film falls down — and where it seems attractive to “bad movie” afficionados — is in the editing. Several of the scenes go on for much too long. When we first hear Mary playing organ in the factory, we get many, many reaction shots from people around the factory. The same is true with many of the conversations, which circle the same point several times. It’s good to have all of this footage, but the editor should have curated it a bit more. Many scenes will drag on far too long, but then we get a stunning over-the-balcony shot of an organ crammed into a warehouse that reminds us why we’re still watching.

Fans of modern independent cinema and shot-on-video horror fans who have not seen Carnival of Souls should rectify this immediately. Bring to it the same appreciation of small budgets trying to do large things and independent filmmakers working outside the system, and you will find lots to value here. This film is essential viewing.