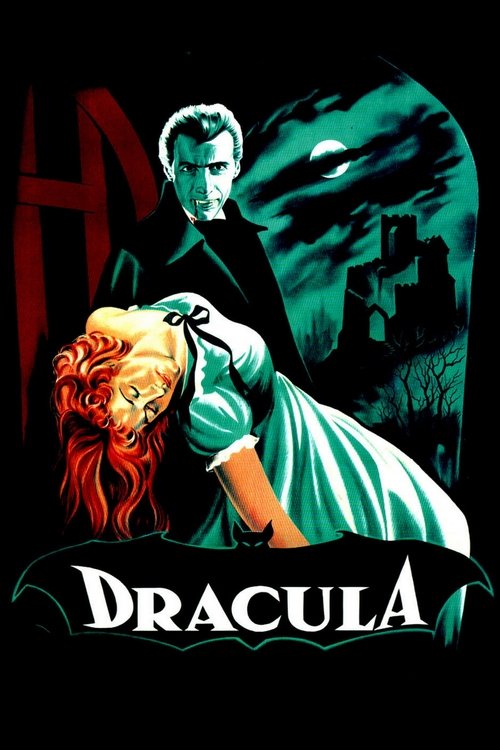

In 1958, Hammer’s Horror of Dracula was a sensation. It had enthusiastic reviews despite some relatively gruesome makeup effects, like puckered bite-marks oozing blood and close-ups of Dracula’s bloodshot eyes. Horror movies were not generally looked on so kindly; in the same year, Fiend Without a Face was inspiring angry hearings in the British Parliament. But Horror of Dracula ranked among the 100 best British films as recently as 2017. Whether Americans know it or not, Christopher Lee’s Dracula --- not Bela Lugosi’s --- shaped our vision of the Count. And yet…

“I can see straight up your nose from here.”

We watch movies with minds two decades into the 21st century. Sixty-three years is a long time in popular culture. Back then, this film’s necklines were daring, and Christopher Lee’s performance was rawly sexual. Enough time has gone by, though, for hardcore pornography to have a mainstream moment and everyone to forget about it. Nowadays, Hammer’s Dracula seems remarkably sexless, even next to relatively chaste vampire movies like the PG-13 Twilight. That may be due to changing mores, but a world that has seen Jim Morrison might have difficulty recognizing Lee’s glowering loom as a turn-on.

Although the eroticism may be difficult to tease out of the film, the subtext about women and infidelity is not. When Arthur leaves his weakened, sickly sister Lucy to “get some rest,” she springs up, flings her windows wide, and then eagerly arranges her nightgown. She is not merely complicit in her own victimhood. Lucy is downright eager. When Mina comes under the Count’s thrall, she disappears overnight and returns radiant. Terrance Fisher recalls his direction to Melissa Stribling: “You have had one whale of a sexual night, the one of your whole sexual experience. Give me that in your face!”

You’d think a Count would at least use a napkin.

The performances by Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing are remarkable. Everyone talks about how Lee redefined the Dracula role, but Cushing’s performance is a different kind of impressive. There’s a long blood transfusion scene that requires considerable technical work with medical props that Cushing handles with apparent expertise. When William Friedkin needed something similar in The Exorcist, he actually hired medical professionals to do the scene.

Nevertheless, “an actor deftly handles medical equipment” is not a compelling argument for watching a movie. Christopher Lee may be chilling, but there’s far too little of him. And even though Michael Gough (Batman’s butler in the 1990s) convincingly plays a boring person, the result is predictably dull.

“I dreamt I had to do Michael Keaton’s laundry.”

Bram Stoker’s original novel is a bit of a mess, and a movie adaptation is a great place to do some ex post facto editing. Unfortunately, the changes here weaken the material further, adding confusion where there was clarity and narrative leaps where there used to be cohesion.

Jonathan Harker is not Dracula’s real-estate agent (as Stoker intended), but Van Helsing’s vampire-hunting partner gone undercover as a contract librarian. When the Count flees the castle to seek out Harker’s fiancée Lucy, he does not take a ship to England but a carriage to the next village over. And he does not move into a new manse, but lives out of the storage room of a funeral home that apparently does not inspect strange coffins --- even if unclaimed for days.

Many older movies feel more relevant, engaging, and even modern. The Thin Man (1934), Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), or The Caine Mutiny (1954) spring to mind. These movies have stronger screenplays and still-relatable themes. The Horror of Dracula’s problem is that it pushes boundaries that moved so long ago few people remember they were even there.

The eyes, in particular, do not withstand scrutiny.