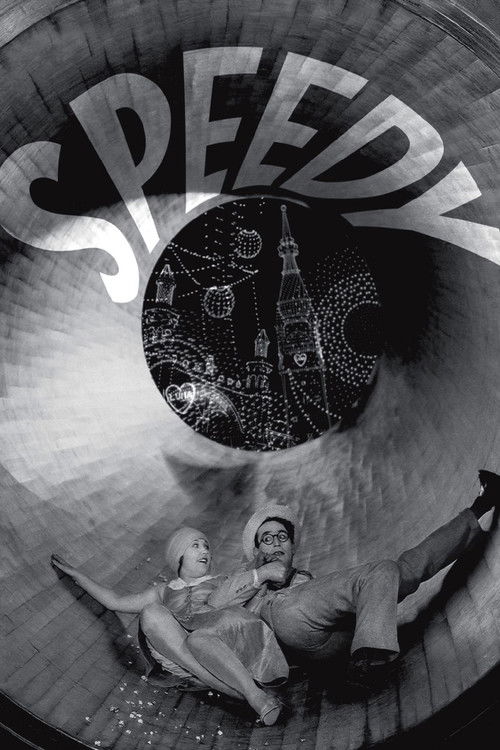

Harold “Speedy” Swift is a young, ambitious, optimistic young man. He wants to get married to his girlfriend, Jane, but she doesn’t feel like she can leave her dad, who everyone calls “Pops,” alone before he’s financially well-cared for. Speedy is eager to make good so he can support both Jane and Pops. An opportunity presents itself when a local streetcar magnate wants to buy Pops’s horse-drawn line. Rather than offer Pops a fair price, though, rich bastard W. S. Wilton tries to intimidate Pops into selling. When that doesn’t work, he resorts to outright theft. Can the eager Speedy actually follow through, save the business, and get Pops his fair share? This is a comedy, so we know of course he can. But it’s the journey, not the destination in this nearly century-old silent movie masterpiece.

Speedy, a baseball nut, updates the pastry cabinet with the latest score from Yankee Stadium.

Since Speedy is a bit of nostalgia for the old animal-drawn streetcars --- almost entirely extinct by 1928 --- and electric streetcars themselves are considered a quaint historical tourist attraction, it’s worth having a little bit of extra context. Electric streetcars had been around since the 1880s, so they were not precisely new even then. New York’s last mule-drawn streetcar was retired in 1917, eleven years before Speedy was made. Pre-sliced bread was first mass-produced in 1928. Betty White was only six years old. The same amount of time separated Speedy from Lincoln’s assassination as this review does Hammer’s Horror of Dracula. It’s no real surprise when Speedy rounds up a bunch of retired Civil War veterans to help take on the neighborhood toughs.

There are sight gags and slapstick, incredible stunts, and extraordinary chase scenes. Much of this was shot on location in New York in an age when cars had taken over, but horse-drawn trucks were common. Harold Lloyd was as well-known in his day as Charlie Chaplain and Buster Keaton, but his own tendency for self-sabotage almost robbed us of this film. Lloyd kept tight control of all of his work, demanded high prices for licensed viewing, and was so picky about the presentation he refused to show his films in theaters that had pianists instead of organists. The movies, he said, were designed with an organ in mind. Lloyd’s films, denied television and theater revivals, fell into obscurity until a rediscovery in the early 2000s.

Seeing the old attractions of Coney Island isn’t the best reason to watch Speedy now, but it is a nice bonus.

My favorite bits were the scenes shot at Coney Island, then one of the largest tourist destinations in the United States. Many of the rides look familiar. There’s also a log flume ride that requires a boatman to paddle the boat back to the drop-off point. But some rides are lawsuits walking. For example, there’s a giant flat turntable. About thirty people get on it. The turntable spins faster and faster, and the riders try to hang on. Ultimately, everyone is flung off.

No one would insure you for this.

Babe Ruth risks life and limb in Speedy’s cab.

Beyond Coney Island, there’s an appearance by Babe Ruth. People frequently call this a cameo, and I expected it to be a walk-on. But no: he’s the centerpiece of one of the movie’s great stunt sequences --- a harrowing cab ride to the newly-built Yankee Stadium. Speedy gets him there barely in one piece. Babe is no great actor, but he’s aided by only having to pantomime; there’s no voice acting in a silent film. “If I ever have to commit suicide,” a title card reads, “I’ll call you.”

Film restoration has come a long way since I first saw silent films as a child in the 80s, and Speedy looks clear, bright, clean, and stable. Returned to near pristine condition, it seems considerably more modern than movies shot late in the next decade. This is in part because the technological requirements of recording sound set cinematography pretty far back. The camera is mobile in Speedy. There are action shots, chase scenes, and special effects. By the thirties “talkies” forced filmmakers back to the studio, with heavy cameras placed statically and stock-still actors clustered around barely-disguised microphones.

Speedy was about six years away from a time where rude gestures would be considered critically dangerous to American minds.

But the other reason the movie seems so much more modern is that there was no national film censorship regime. In fact, there’s a scene where Speedy flips the bird to his fun-house mirror reflection in what is possibly the first motion recording of the gesture. I was so surprised I didn’t actually believe what I’d just seen; it seemed as out-of-place and anachronistic as the roller-coasters. In about six years, the Hays code would be in place. This extraordinarily prudish filmmaking era would stunt film-makers’ ability to make movies that seemed anywhere near as natural and human as Speedy’s relationship with Jane until the late 1960s.

If you are unfamiliar with silent movies or do not watch old ones, do yourself a favor and seek this one out. Despite its age, it is still one of the best movies I have ever seen from any era. It is an absolute masterpiece of slapstick, a sweet story, and the condition you can see it in now is probably better than any of its original audience ever experienced.